Table of Contents

Deep Maps

Making a Deep Map is a way to be conscious of a place in such a manner as to hold multiple layers of understanding of the present moment in a non-reductive and robust manner. This is in contradistinction to the ways we normally speed through and consume the landscapes and places of our petroleum-driven, industrialized lives, and the related sense of self this produces. A Deep Map of a place includes many things: direct perceptions of that place; its inhabitants’ memories; embodied understandings as place enters you in numerous ways that are emotional, psychological, physical and transcendental; geological formations; non-human actors like animals and plants; historical developments from different eras; weather patterns; agricultural uses; modern infrastructure; bioregional processes; contradictory ideological ratiocinations; and more. A Deep Mapping of a place potentially has no limits to complexity as long as it is meaningful and you have—or a group has—the ability to hold an awareness of the varying ways of understanding. The layers can be added as long as this helps elucidate and makes present a complex way of relating. This short text describes where the idea of a Deep Map comes from, and how it can be developed further and applied as a methodology in direct social and spatial encounters.

The idea of a Deep Map, as an emergent method—and cultural formation—for thinking the world in terms and ways that work to eliminate petro-subjective positions, is directly inspired by William Least Heat Moon’s book PrairyErth (a deep map) (1991). In the book, he describes borrowing the ethnographers’ process of “thick description.” This concept was introduced by anthropologist Clifford Gertz in his book The Interpretation of Cultures (1973). A thick description enumerates a culture and its behaviors, while it simultaneously gives a dense context so that the behavior becomes understandable to those not a part of the culture being described.

Least Heat Moon’s use of Deep Mapping takes on a powerful literary approach to understanding a place. PrairyErth tells the story of several counties in Kansas that once thrived, but are now in severe decline with few denizens. Least Heat Moon creates incredibly dense contexts for telling the stories of the current inhabitants and what might motivate them to stay as things continue to decline and the world changes around them. Least Heat Moon starts each exploration of the various Kansas counties he covers in PrairyErth with a bevy of quotes. He takes them from historical records, daily newspapers, poems, philosophy books, and many other sources from the local culture as readily as elsewhere. These quotations begin to sensitize you to the many things he will be talking about in the pages that follow immediately after. In presenting you with a particular place, he might describe important geological formations, then move on to how the indigenous people used the land, their displacement by settlers, the fast industrialization of the place, and then the decline of the modern economy, which sets the stage to meet people who have stayed in towns that are mostly vacant and falling apart. The book is a dazzling achievement that makes the stories of these places thrive and become tangible, almost a shared reality with the people he talks to.

How to Inhabit a Deep Map

I am an artist and am interested in how I can make cultural tools that help shift us out of one way of being in the world into another that is less violent and destructive, which can help us survive climate breakdown and chaos. Instead of making art that you look at, I make work that you experience directly in a cultural way, very much like you would if you went to a concert where you were asked to sing and clap along the entire time. Your presence and your expression of yourself are critical to the success of the gathering. I have 20 years of experience working as an artist in groups and making art collaboratively. This has given me a lot of experience in facilitating all kinds of group processes to amplify the subjects explored.

I use Deep Mapping as a cultural tool that can help shift our behavior and allow us to experience what it might be like to have petroleum out of our sense of self and the kinds of social formation we nurture. Least Heat Moon makes Deep Maps with writing; I have borrowed this notion to carefully craft immersive experiences to be shared and gone through with others. They have been organized and realized with the explicit purpose of practicing the de-industrialization of our individual and collective sense of self, to begin to understand what post-oil subjectivity might be. I have organized long camps and workshops where a Deep Map is created for people to enter.

Inhabiting a Deep Map is a social process, a pedagogical tool, and a way of tuning yourself to the complexities of being in any place. I work to convey a strong sense to the people who join the camps and workshops that they will be experiencing the given place we are in in a way that differs dramatically from petroleum-based space and time, which flattens places and our experiences of them.

I co-organized a camp in rural Scotland, in the summer of 2015, that focused on the dramatic landscape that surrounded the Scottish Sculpture Workshop (SSW), the venue that hosted the gathering. This landscape is heavily industrialized, yet maintains a beauty and mystery that gives one a sense that it could be restored and understood in radically other ways. The camp lasted 11 days. Around 30 people attended. We engaged where we were with embodied learning processes. We used exercises that come from a variety of sources. One of them that is used frequently is Deep Listening. It is a practice developed by the American composer and electronic music pioneer, Pauline Oliveros, to train ourselves to use our vast perceptual capacities to sense sounds, energy flows, and ancient rhythms in ourselves and the world. A simple beginner’s exercise—that has many similarities to meditation, but is directed towards the outside world and not one’s inner peace—is to sit and listen for 30 minutes to all the sounds one hears moving from the global (hearing everything at once) to the focal (listening to a specific sound until it stops). The results are always quite surprising. Thirty people listening all to the same sonic environment in this way will each come up with very different understandings of what it is they heard. It become immediately clear that the wildness of existence is just on the other side of a very permeable threshold!

We combined these exercises with discussions about climate breakdown and our fears about the future. We read and discussed texts that sensitized us to various issues like animistic knowledge and how to regain the powerful tools of sensing the world that we have evolved with, but suppress with regular calls to being rational about everything. We had guests come and talk about a variety of subjects that included land reform, soil and spirituality, re-inhabiting rural Scotland via the tradition of hutting, and more. We had workshops where we walked, with Nance Klehm, around the small town where SSW is located and learned empathic tools for understanding plants and their characters in addition to the medicinal properties of these plants that were growing in the cracks of sidewalks and in alley ways. Another workshop, led by soil scientist Bruce Ball, had us looking at soil samples everyone was asked to bring from their homes so we could understand how the soil worked and how to gauge its relative health. We made excursions to a nearby permacultural farm. We took a longer trip to an enormous rewilding initiative, on 10,000 hectares—by an organization rewilding the Scottish landscape—Trees For Life that is restoring the Caledonian forest on a former estate where over grazing and hunting for many generations had destroyed much of what had been there.

We had a sauna made so people could relax after the long 12 hour days of activities. The interior was made from locally harvested larch and the rocks that sat on the wood burning stove came from streams, fields and the hills surrounding SSW. The exterior was made from old whiskey barrels and had an amazing smell every time it rained. The sauna was used by artist Mari Keski-Korsu to do whisking and heat balancing for those who wanted it. This is an ancient Baltic healing tradition that she is trained in. Keski-Korsu made whisks from various trees that were in the hills surrounding SSW. A typical session went like this: you would sit in the sauna with Mari for 30 minutes, exit and cool down a bit, then reenter. You would lie naked and face down on a pillow of aromatic leaves. Mari would then whisk your body, swirl heat from the top of the sauna down over your body, and then massage parts of your body with the tree branches. Next you would turn over. A hot bunch of leaves put on your genitals. More clumps of hot aromatic leaves put over your face. And even more put under your arm pits as Mari continued to move the hot air over your body, beat the soles of your feet, and literally melt your consciousness into a completely other place. Keski-Korsu also introduced the group to animal communication via a workshop with Clydesdale horses, which were used for centuries to work the landscape.

After many days of being constantly immersed in these kinds of experiences, a relatively strong group cohesion emerged for most people as did an alternate sense of place and time. This was not just my own perception, but something that was communicated to me directly or in passing when I overhead others making statements that revealed this, particularly about their shifted sense of time. This has been an organic part of all the Deep Map situations I have organized. Each group arrives at this state at a different moment, but they do get there and the Deep Map is an important part of this.

Extending Deep Mapping

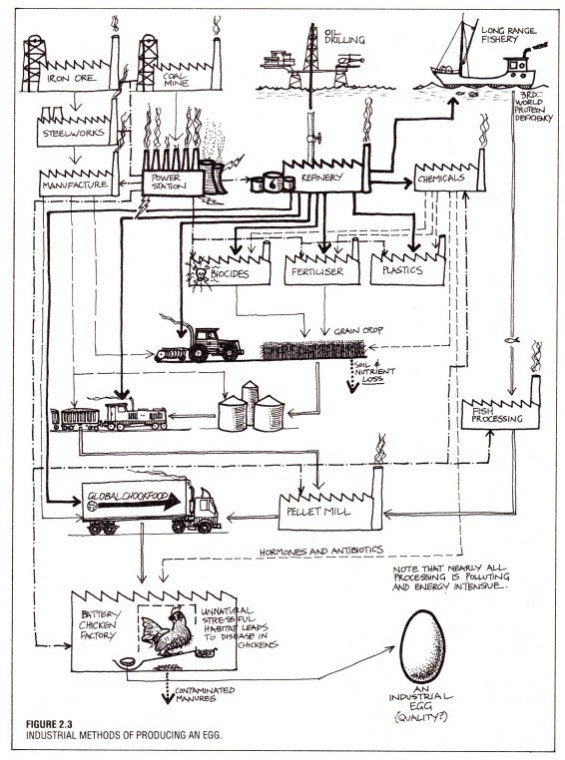

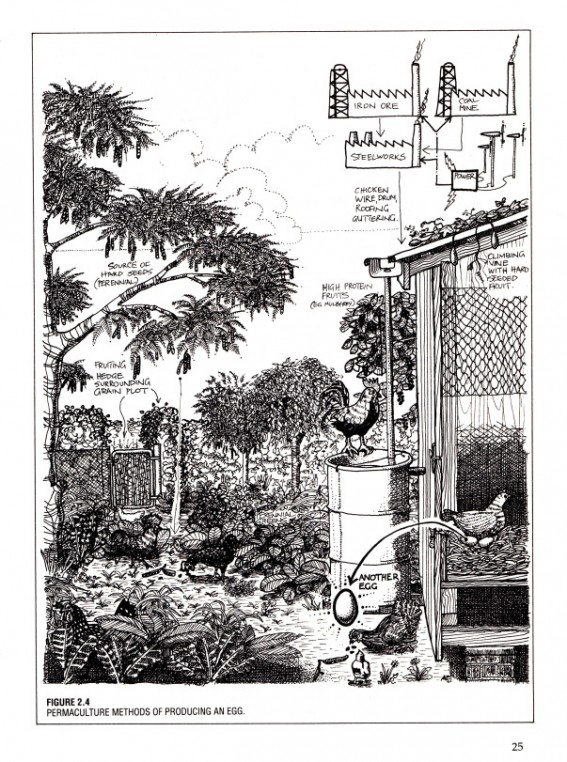

Permacultural resource mapping can be used to help visualize aspects of a Deep Map. These processes are highly compatible and are very powerful when combined. I am constantly inspired by illustrations from the Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual, by Bill Mollison (1988), in particular two maps that show the production of a single chicken egg. One shows an industrial egg and all the resources that go into making it, complete with all the energy intensive and wasteful processes like the burning of fossil fuels to make many of the materials needed to house, feed, transport chickens. This map is contrasted with a another that shows a permacultural egg and how its making dramatically reduces the wasteful and polluting energy inputs needed by creating things like self-generating food sources that feed the chicken as the chicken’s waste feeds it, and so on.

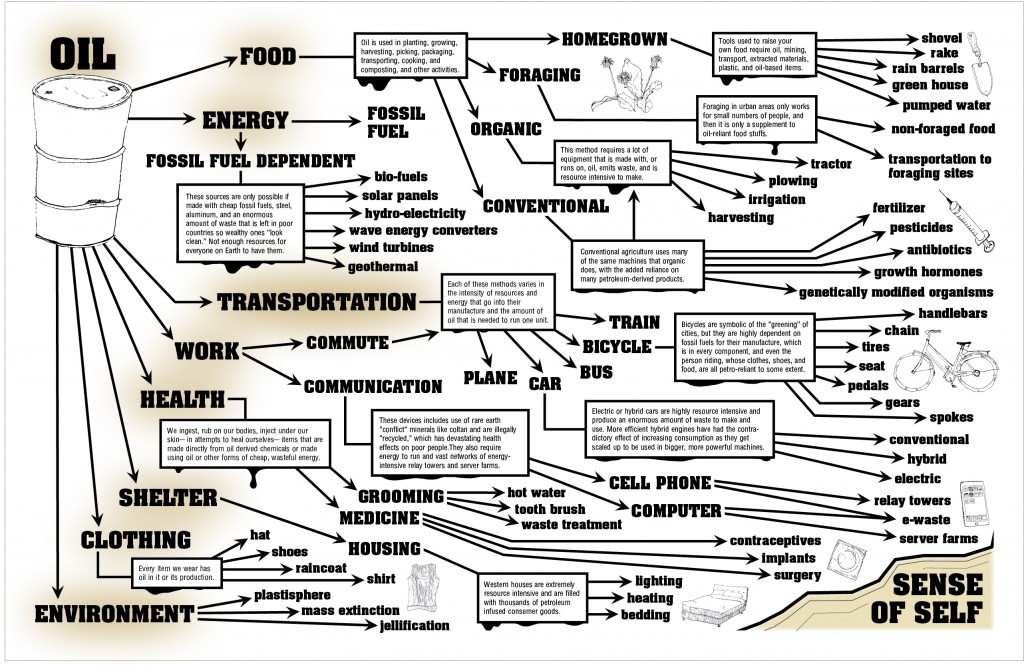

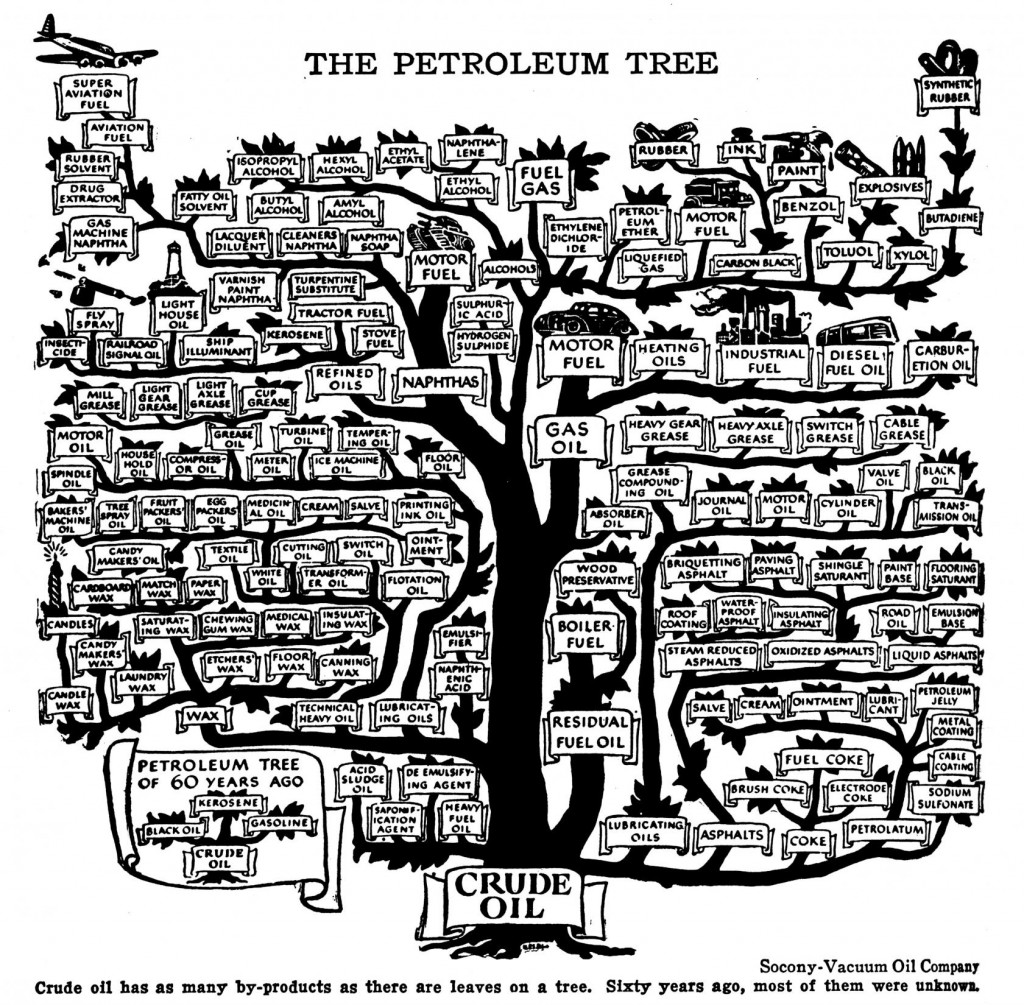

An example of using permacultural resource mapping that I have used in the gatherings I organize, is the Petro-Subjectivity map. It presents all the intersections in your life with oil and its presence in every imaginable process and action.

Instructions for making a Deep Map

Making a Deep Map takes a significant amount of time to organize and construct. It requires a commitment of resources, finding collaborators, and creating a situation where one is a facilitator among other facilitators. Everyone involved in some way becomes a co-creator of meaning and experience. The Deep Map enables an experience where no one person, discourse, or narrative holds power over an understanding of the things you are investigating. They are combined, piled up, and co-exist even when they seem to be contradictory. The Deep Map gives participants immediate, directly embodied participation in the subjects and leaves them with an understanding that is not possible otherwise.

1. Start by organizing an extended, immersive gathering—like a camp*—where there is a lot of time to explore a specific set of concerns from multiple perspectives. The gathering can be for a 3-day weekend or much longer. This can happen in a city, and is an option which deserves experimenting with. However, a rural location makes for greater group cohesion and concentration as people will be taken away from the stresses and demands of their urban lives.**

2. Explore topics in several different, overlapping, layered ways. Make space for people who use multiple, and contradictory, kinds of “languages” for understanding the world, for example: academic, activist, spiritual, myth-telling, empathic, visionary, scientific, or any combination of these.

3. Explore topics through multiple kinds of activities: lectures, directly embodied learning, walks, discussions, readings, hands-on workshops, team building exercises, interspecies communication, and more, to address your set of of concerns.

4. Have your activities unfold in a variety of settings. You can have multiple discussions, for example, but try different social formations to do this: formal presentations in a circle, a loose gathering around a bonfire at night with food and drinks, on top of a high rise building, a moderated discussion on spectrum,*** plus many more ways.

5. Take care to provide a thoughtful blend of variation and repetition. It is good to have too much happening so there is this feeling of being overwhelmed, but makes sure it is in a positive way. Give people the freedom and feeling that they can opt out of things if they become overwhelmed. Reassure them that there is no judgement if they need to take a break and take care of themselves.

6. Take excursions to visit people, initiatives, landscapes or anything else that offers yet another perspective or way of considering what it is you are exploring. This puts people into an additional dynamic situation that you have not organized, but will only amplify your other activities.

7. Figure out the economics of the Deep Map gathering. This is relative to the ambition and scale of what you want to organize. Deep Maps can work both with grants where people have only to pay for a little bit of the gathering, or maybe you have to ask people to cover all the costs of transportation, food, speaker fees, workshops, etc. Keep it affordable for participants if you can.

8. Decide who you want to invite to your Deep Map. This will effect what you organize and the kind of experience you have. You can have an open call and accept anyone who answers the fastest. You can have folks answer questions that show their level of engagement with the subjects you are exploring and then make a curated selection. Perhaps you develop a different strategy to bring people in, but it is good to give this aspect of organizing a Deep Map enough consideration.

9. Make Deep Map guidelines.**** They can be as minimal or as detailed as your gathering requires, but should be used to help strengthen and support the success of the Deep Map.

Notes:

* A great resource for understanding the history and forms of camps and their potentials for being used in a variety of capacities, for making Deep Maps, and other things, is Charlie Hailey’s Camps: A Guide to 21st-Century Space, MIT Press, 2009.

** Commuting restraints were so severe in London that it cut a lot of time off of when we could start and end our days together. In Helsinki, people were distracted by the proximity to their “urban busyness” —the fear that they might be missing out on something else—and it effected the cohesion of the group.

*** This is a specific kind of discussion used by activists to visualize the various positions people represent in a debate. In the space where you are holding your discussion, you designate two extreme positions in a debate and give them a physical location, perhaps by marking the spaces with chairs. You ask people participating to locate themselves at or between these two points. The discussion is facilitated and draws out the differences as a way to discuss the issues.

**** An example of Deep Map (Camp) Guidelines:

- This is a place of respect for differences in race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, ideology, temperament, pace, ability, introversion and extroversion.

- We practice discourse diversity, in the sense of biodiversity, and the necessarily complex set of experiences, cultures, education, and so on that shape each of us.

- We have respect and awareness for the non-human participants in the camp at the site and anywhere we may go.

- We work together to make this a safe space for you and for anyone at the camp. It is important to take care of yourself, to make sure you are healthy, and that you are not stressed out by anything at the camp. Take time away if you need to from group situations and processes. Ask for help should you need it.

- This is a place for constructive, generous criticism, reflection, and pushing each other to learn and understand in an intense yet nurturing manner.